Adventure Design Checklist: Part 3

I originally started this series about a year ago when deciding to publish my NAP:II adventure Temple of the Beggar-King. A lot of life stuff has happened between then and now, causing me to be delayed in getting my adventure out, but I am glad to say that after having the time to pick that project back up, the end is near.

I thought I’d also try to finish this Adventure Design series I started writing.

So far in the checklist I have blogged about the following:

Good Encounter DesignAdventure SummaryWhat is really going onAdventure HooksSpecial RulesThe ApproachLevel DesignEncounter Variety and PacingTicking Clocks

Informational Viewpoints

The Map

Treasure Distribution

Ticking Clocks

I think in every adventure it’s good to think about ticking clocks; that is, things that will happen once the players show up, regardless of how little they do; consequences that will occur as time ticks down.

This could be a literal ticking clock, like in three-days-time the maiden will die; or, the dungeon will flood next high tide, but doesn’t need to be. Regardless, I think a good adventure should have a sense of poised dynamicism about it. Where if the players take up the call to adventure and arrive on the scene, even if they leave right away, something should happen. I find the best adventures no matter how static they may seem at first, are really more just a carefully balanced stalemate. It’s the players arriving and interrupting this stalemate that causes consequences and causes the ‘plot’ rather than a series of planned out events.

I think this often leads to good design as it forces an adventure to have factions to some degree or another. Different sides and viewpoints which have differing goals.

Time should feel like it matters during an adventure. Even if it’s an old and forgotten tomb, it should still feel like there will be greater consequences besides loss of life and limb if the players either stay too long or leave too abruptly.

There should be something at stake in every good adventure, and what’s at stake should be impacted by the passing of time.

In my adventure, Temple of the Beggar-King, there’s not a lot of explicit ticking clocks. It is a fairly static site: an old and ruined temple. I provide a simple enough sense of possible consequences. However, in the hooks and background information there is a sense of an escalating danger:

The Beggar-King is locked away in meditation because long ago he had a revelation. As he delved deeper and deeper down the chain of past lives, he realized at some point he would arrive at the very moment of creation, the moment when one is all, and all is one; the primordial form. It is in this moment he could free himself from the chain of being, achieve a greater enlightenment, and break from the lattice of time itself. His traversal is starting to unravel everything.

Due to the Beggar-King's meditations unraveling the lattice of time, some souls are being reincarnated with full memory. Strange cases occur where babies are born capable of adult speech and thought. However, they are mentally broken from the incomprehensibility of what lies beyond death. They wail and cry, rambling of past experiences, wondering where their loved ones are, recalling the last moments of their death, and wanting to return ‘home’, all before falling comatose. Forgetting is a blessing.

It’s not explicit, but suggests enough that if the players decide to stop investigating the temple halfway through, the Referee can start having things happen to kind of indicate that things may not be done yet, that there are still consequential things happening that lead back to the temple.

In the section I wrote about approaches I said I think it was important to describe the approach to an adventuring site, even if it’s meant to just be slotted into the Referee’s campaign, because describing the approach can help the Referee understand the themes of the adventure and help place it in their world. In this manner, so too can thinking about and describing the ticking clocks help the Referee place the adventure. Except instead of in space, in time.

Thinking about and writing about ticking clocks helps the Referee understand how static or dynamic the adventuring site is going to be; how much output they’re going to get out of the system for the input the players put in.

If a site feels a bit static that isn’t necessarily bad. Sometimes that’s exactly what a Referee is looking for; a static site the players can delve into, get entangled with a bit, before moving onto the next site. A place that the players can explore and do a lot in with minimal consequences. A place that the Referee doesn’t have to think much about or prep too much.

Sometimes, the Referee is looking for something more; they want a site that has lots of factions with clear goals, a site that’s a veritable powder keg waiting to blow, a place that’s going to have a lot of consequences for the players with minimal input from them. A place that while there’s probably more for them keep track of and prep for, is going to be more interesting as a result.

Thinking about and describing ticking clocks will help a Referee discern where upon this continuum the adventure lies.

Informational Viewpoints

I find informational viewpoints are way more common in more visual mediums like videogames or movies. In movies they’re basically establishing shots. In videogames they generally times when the player arrives in a new location, usually at a viewpoint, and then can see the entire location with points of interest laid out before them.

I don’t know if RPGs really have an equivalent, especially in dungeons. It’s really hard to describe multiple locations at once via text. I attempt this a bit in one of my dungeon rooms that’s a large cavern. This is the first description you get upon entering:

The soft glow of hanging lanterns crafted from sandalwood cascades through the darkness. A brook trickles through the center of a gigantic cavern, a gentle mist rising from its surface. Long pale grasses grow on its shore and white petals float on its surface in shadow. A gravel path winds its way up towards a low pagoda on a hill.

As you can see it highlights the brook, the path, and the pagoda on the hill. It’s written in a way that it directs the eye from where the player is standing towards things upon the horizon. I think this is the best way to describe such a scene, you want it to feel like a well composed painting where the eye naturally follows a path and is drawn to different elements, flowing from one to the other.

I do think this room is cheating a bit as most dungeons don’t contain large cavern rooms with points of interest. They tend to be smaller more discrete rooms. However, I do think it kind of highlights how important thresholds are in dungeons.

In the level design section in Part 2, I describe how a dungeon’s rooms should be organized into zones. Rooms generally serve a purpose and a series of rooms close together with lots of connections probably all serve some greater purpose, like a Servants Quarters may have different types of rooms but all deal with things a servant does or needs to live.

Naturally if you have a zones of interconnected rooms that all serve a general purpose, connecting these zones you’re going to have thresholds. These thresholds should somewhat serve as bottlenecks. While I do think it’s good to have more than one entrance and exit from a zone, in real life, different zones, even if in the same building, tends to be fairly compartmentalized. Bottlenecks connect them and are useful.

It’s in these threshold locations that I think the greatest opportunity is to provide an informational viewpoint. The players should get a sense that they are literally going from one zone of the dungeon to another, that the place they were in served a bit of a different purpose than the place they are going into.

You can highlight this numerous ways; a change in architecture, the presence of some kind of guardian or obstacle, signage or some other form of information, an actual viewpoint, some form of map, hints at what inhabits the new zone, hints at the purpose of the new zone.

Overall I think defining thresholds and giving players information at what zone lies ahead is important because it helps gives an idea of what to expect in this new area, of what’s important, what they might encounter. It helps build suspense and themes.

The Map

Oh, maps. Pretty much included in every adventure, but often somewhat overlooked. This is kind of another nuts-and-bolts thing. Include a map of the adventuring site, even if it’s just a pointcrawl style map. Pointcrawl style maps I think are oftentimes more useful than hexcrawl style ones. If you can’t really put your adventure down on a map, or it requires many, many maps, then it’s probably not an OSR style site based adventure and will need refinement if you wish it to be.

Beyond this I can think of following general advice:

Don’t make it too artistic. I think it’s better to be clear and readable then artistic when it comes to maps.

Maps should describe architectural features, not room contents. That’s kind of what the room description is for.

Maps should show hidden doors and hidden things, but these things should also be and hinted at and clues provided in the room descriptions. For example, if there’s a secret door in a wall, the room description should probably describe a draft coming from that area and give something for the players to investigate. The fun part of secret doors isn’t that the players don’t know there is one, its them trying to figure out where it is and how to open it.

Maps should contain a grid with a scale. I don’t need to know the dimensions of each room as players enter it. Neither do the players. If I need to know that information or the players want to know, I can just look at the map, count the squares, look at the scale, and figure that out for myself. People tend to not think in raw dimensions, you’re way better off giving the sense of scale of a room through the proportionality of it’s contents.

Maps should be labelled and have a legend.

Maps should contain the number and names of rooms. Each room should be named with a name that gives a sense of what the room is about and in an evocative way that sticks in the mind. Throne Room is okay. Red Velvet Throne Room is better. The label on the map should be the same as the title of the room description.

Maps should have the entrances and exits labelled. They should indicate how to go from one level to the next.

Each page or spread of the adventure should contain a mini-map that relates to the rooms on the page. Yes this is more work, but it makes the adventure way more useful at the table where the Referee doesn’t have to constantly referee to the large map which may be hard to juggle with the text.

You should always provide a player facing map (map without important Referee only secret stuff). This way if the Referee wants to give a map to the players they can. Or if they’re playing online and want to reveal parts of the map as the players explore, they can without revealing secret things.

Treasure Distribution

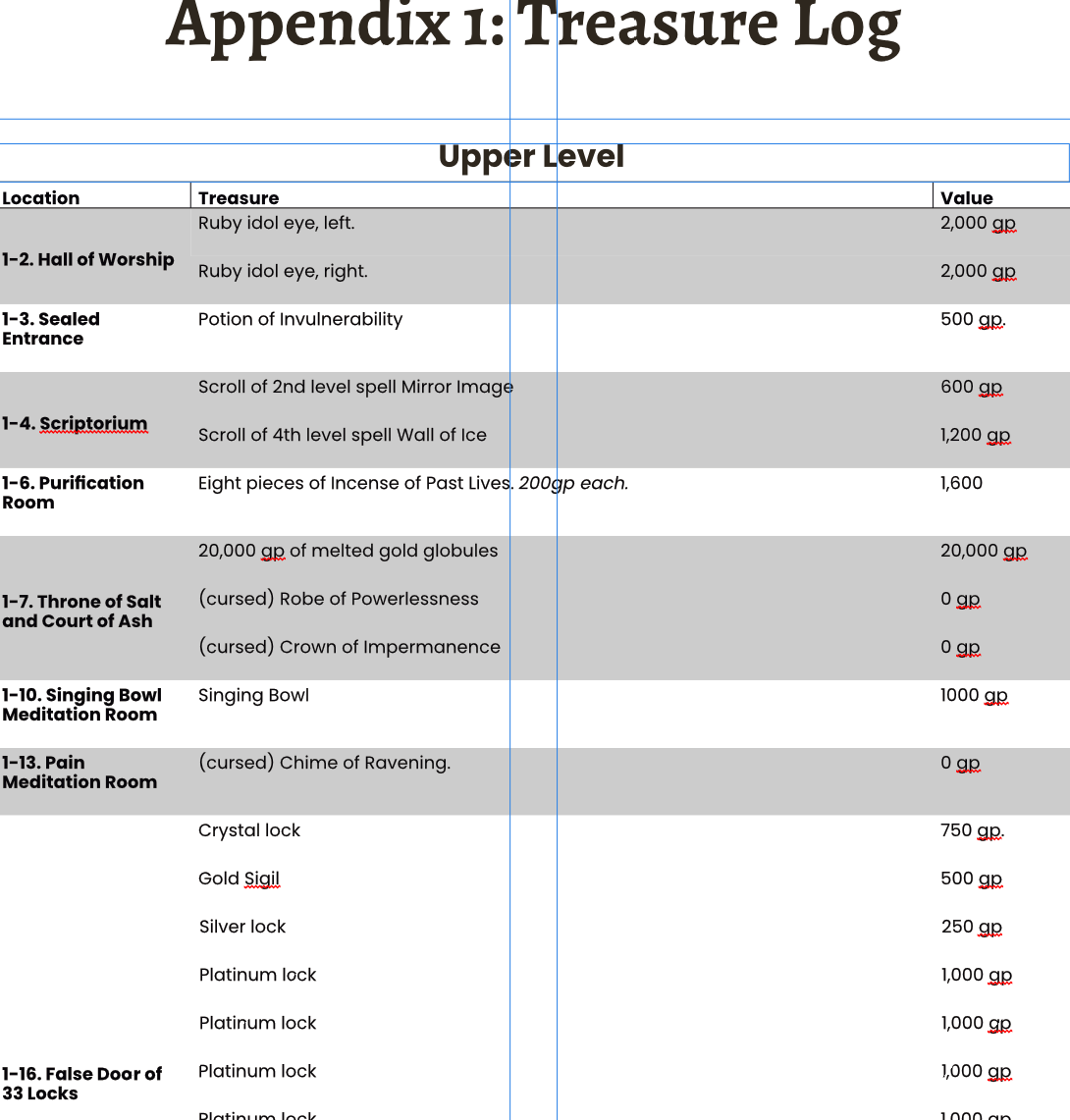

I think it’s important in OSR games where 1 gold = 1 XP, to give a log of all the treasure in the adventure. It should detail the treasure, it’s value, and where it can be found. I do so in Temple of the Beggar-King:

This severs several purposes. The first is to get you, the writer, to actually do the math and calculate how much treasure is in your adventure and figure out if it’s enough for a party of 4 at the level its supposed to be for, to actually get part way to the next level. Something you should be doing. I read way to many adventures that contain far too little treasure.

The second reason is to serve as a reference for the Referee to quickly lookup the treasure and read what it’s about. Far too many times my players will pickup magic items and then a session or two, when they are on another adventure, ask about them and what they do. I then either have to try to remember (or more often, make something up), or try to quickly flip through the previous adventure to find out what that item they found actually did.

The third reason is to consider how much of your treasure exists in caches. I think it’s way more fun and interesting for players to score a bunch of treasure at once, then have it doled out in equal amounts in every room. While getting through a difficult room with no obvious payout can be frustrating, I think coming across a big score is psychologically rewarding enough to make up for it. It helps to keep players guessing and engaged where if a room or two sucks, they’ll probably still press on cause they know it’s only a matter of time before they strike it big. Big treasure caches should be obvious and fairly easy to obtain once you find them. They should be purely a reward, not tricky bait.